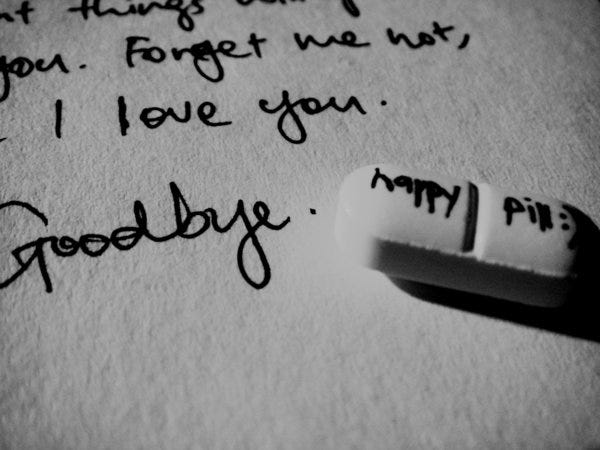

Princeton professor Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.’s book, Democracy In Black, begins with a meeting he had with three cofounders of Millennial Activists United, one of the youth groups that kicked off the uprising in Ferguson, which in turn catalyzed the nationwide Black movement. Before Michael Brown’s murder, one of the young women, Ashley, told Glaude, every day was about making a determination to stay alive, while “‘Counting down the hours until I’m going to shoot myself.’” According to Glaude, “Alexis and Brittany stared at her as she talked, as if Ashley was describing all of them.” Ashley continued, “‘Now it’s like … [Y]ou can’t kill yourself today, because you got to do this. You’ve got this meeting, you’ve got to go protest at seven o’clock.’”

Reading this account gave me chills. It was not only the realization, which maybe should not have taken so long, that the brilliant and charismatic young leaders of this movement teeter on the edge of suicidal despair, but the fact that I recognized their despair. I had gone through it myself. I read that as someone whose life has been saved numerous times by the chance to be part of a “movement moment,” and as someone painfully aware of how fleeting those moments can be.

Mayer Vishner would also have resonated with Ashley’s story, I suspect, if he had lived long enough to read it. Two weeks ago, at the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival, I saw a documentary about Vishner’s life, and death. A core member of the Yippies, one of the most theatrical and glamorous elements of the 1960s political counterculture, Vishner committed suicide in 2013, after battling depression and alcoholism his entire adult life. An obituary on the website The Villager, reported that “Mayer was heartened by the Occupy Wall Street movement but was disappointed that his skills of ‘phone tree’ organizing were obsolete in the age of Internet social media.”

When the Vietnam War wound down and the huge social movement it catalyzed among young white people followed suit, Vishner seemed on his way to a career in the flourishing alternative journalism business. He became managing editor of the L.A. Weekly. But he was fired for alcoholism and never managed to either dig his way out of or manage his addiction. Or likely the addiction was a symptom of the larger problem, that he never figured out a way to live without the movement.

Justin Schein’s thoughtful film at one point flashes through other notable suicides among Vishner’s cohort: comedian Lenny Bruce, folk singer Phil Ochs, political leader Abbie Hoffman, underground journalist Tom Forcade. The film raises the question: Did the movement and its eventual demise lead its participants to suicide, or did it simply attract people who were likely to become suicidal?

I would say the answer is both. Vishner’s despair was rooted in isolation and loneliness. Many of us who are drawn to activism have poor social skills, or at least, we have trouble connecting with people through casual conversation. We’re intense. The subjects I’m most interested in discussing and most knowledgeable about (Palestine, queer liberation, radical feminism, reparations) seem like highly inappropriate topics of conversation to “normal” — i.e., nonmovement — people. It’s not that I don’t know that, but I can’t deftly shift into a nuanced debate about “Love & Hip-Hop” or “Dancing with the Stars” because I don’t watch them. (If they happen to be “Project Runway” aficionados, I’m in luck.) Even if we are talking about novels, I am likely to use examples or frames that don’t make sense to them. And since I’m not pretty, they have no particular desire to talk to me anyway. (Of course, not everyone in the movement has that problem.)

Our social awkwardness is both a cause and a product of our alienation from the dominant society, making it possible for us to see its flaws clearly, and drawing us to others who are passionate about its destruction.

Movement work throws people together in intense situations, where our deepest qualities and most useful skills quickly emerge. People learn how they can count on you (if they can). Sharing your opinions no longer sets you outside the group, but draws you further inside. We come alive, sparkle with confidence, and exude pheromones. As Ashley’s remarks to Professor Glaude suggest, the frenzied activity keeps your energy high and leaves scant time for brooding.

But movements inevitably fray. They fray because the passionate ideals that bring us there make us impatient and touchy when people don’t see the work in the same way as we. We put ourselves on display, give our hearts and souls and sweat to the group and it’s easy to feel unseen or underappreciated. And this brings us back to our sense of alienation.

They also fray because the emotions that keep us going at that fevered pitch, especially rage, are exhausting, as Debbie Gould’s excellent book, Moving Politics, illustrates through the case study of ACT UP. Rage is in part, though certainly not entirely, a shield against the intense pain that oppressed people carry, pain that is also a source of the alienation that drew us to the movement in the first place. As the movement frays, our alienation and isolation seep back in, often leading to further schisms.

Not all such fraying is fatal to groups or networks. Some are able to knit themselves back together and come out stronger. Others fracture. There is not only the interpersonal stress to overcome, but also changing conditions to adjust to. Sometimes the method or focus of the group becomes obsolete, like Vishner’s phone trees (although I think most groups I am part of these days could use some phone tree organizing). Movements can be victims of their own success, failing to find a new direction after a victory.

The Movement for Black Lives and its component groups and networks seem nowhere near burning out. In fact, by all indications, they are only now coming to full strength, with the release of their comprehensive platform. But while that may be true on a national or international level, it might not be true in every community or for every organizer and activist. I worry about the young people whose lives are so clearly dependent on the movement’s thriving. I worry that more of them will come to a day when, like MarShawn McCarrel, their demons win. I worry that government elements will exploit rifts between them and the stress of the work to push them to the breaking point. I worry that repression will beat down on them, as it did on Aaron Swartz, who apparently could not face the prospect of years in prison.

In periods of deep fracture, people are thrown back on the resources they came in with. Many white activists who committed to violent overthrow of the government in the late sixties and early seventies were able to move on to professional careers, like Bill Ayres, Bernadine Dohrn, Mark Rudd and Kathy Boudin. Many of their Black and Native American counterparts, like Herman Bell, Mutulu Shakur and Leonard Peltier, received far less tolerance for their youthful misadventures. Even Vishner might not have lasted until his sixties, had his mother, whom he hated, not paid his rent for decades, turning the responsibility over to his brother when she died. During the Occupy season, I knew young people who gave up jobs and moved out of precarious housing, to live full-time in the camps. When I asked what they were going to do when the camps were busted or broke up, they waved off the prospect. The Movement would provide, they said vaguely. They couldn’t imagine that it wouldn’t last until the revolution. I don’t know where some of them ended up.

I also worry that the tools of today’s organizing, while allowing movements to swell and spread much faster than in previous eras, don’t provide as much shelter from the storms of depression. What has kept me going all these years, until I no longer feel like I’m on the ledge, is that the connections I made during those heady days of nonstop meetings and protests were deep and personal. I found lovers who became friends and family. We spent hours and hours together over years and years. We know how each other likes their coffee and what their favorite ice cream is. My movement friends were the ones who first taught me that my birthday was on the peak day of the Perseid meteor shower, whisking me off at 1:00 am on my thirtieth to go to Tilden Park and watch the stars streak across the sky, while debating whether we would go if the alien ship came to take us away. The same people organized protests when I was arrested in Palestine, picked me up at the airport when I was deported, cared for me when I was getting chemo and threw a party when my book came out.

For sure, I have seen some of those deep ties forming among the folks in the Anti-Police Terror Project and the Black Leadership Committee here in Oakland. I’ve read about couples, like Alexis and Brittney, and close friends like DeRay and Johnetta. But there are many others around the edges who are recruited and get engaged via the Internet who may not have a group in their community, and might not be the kind of person who can organize one on their own. Debbie Nathan’s excellent piece, What Happened to Sandra Bland, offers a picture of what that can look like.

This is not meant to be a downer. It’s meant to be a call to action. To solidarity, to support, to love. If you know people who are movement people, don’t assume they’re fine just because they seem so cool. Remember their seeming snottiness may just be those bad social skills. If you have the means and the inclination, follow the example of whoever created the “Stay In It Fund,” offering small stipends for women with kids to continue their movement work.

It’s up to us all to make sure both the movements, and the people in the movements, stay alive.

Once again you touch my heart with your words and wisdom.

LikeLike

Back at ya.

LikeLike